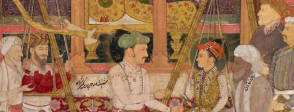

Weighing a prince

In his memoirs, Jahangir describes several weighing ceremonies, stating that this was a tradition begun by his father Akbar. The emperor or one of his sons could be weighed several times against different precious goods such as gold, silver, cloth and grain. These goods, or coins of equivalent value, were distributed to fakirs (itinerant holy men) or to those in need or were used to pay for building projects. The tradition was continued by prince Khurram when he became emperor Shah Jahan, famous for later building the Taj Mahal.

Emperor Jahangir and Prince Khurram are at the centre, with the prince seated on a large scale decorated with gold, rubies and other jewels. Before them on trays are folded cloths, daggers, jars and other gold objects studded with jewels. Two more trays contain necklaces of precious gems. Officials stand beside the prince, identified by name with tiny inscriptions. In the foreground a treasurer notes the proceedings in a book. All stand in a courtyard beneath a canopy, with the title of the image in Persian inscribed above.

Religion

This was a religious occasion. The weighing ceremony took place at an auspicious hour, as calculated by astrologers, and holy men present made blessings and prayers during the weighing. The Mughal rulers were Muslim, but the weighing ceremony probably derived from a Hindu ritual. This appears to reflect the policy of religious tolerance adopted by Akbar and continued by Jahangir. As Akbar expanded the Mughal empire, taking control of majority Hindu kingdoms, he was able to maintain strategic alliances with subjugated Hindu rulers by allowing them regional authority and religious freedom. Akbar and Jahangir had Hindu generals in their armies and held regular meetings with Muslim and Hindu holy men, publicised through paintings such as this one, which communicated their strategy of religious inclusion.

Wealth and power

Whether the precious items on display were there to be weighed or as gifts for the prince or are an artistic effect, they demonstrate clearly the wealth and status of the Mughal court. Jahangir and Khurram are finely dressed; they wear necklaces and daggers with jewelled hilts and have haloes of light around their faces, denoting their imperial status.

Jahangir’s father, Akbar, had vastly increased Mughal territory, capturing the Muslim kingdom of Bengal in the east and Gujarat and the Rajput kingdoms in the west, as well as much of present-day Pakistan and Afghanistan. His conquest of the Deccan, the rich states of central India, increased Mughal wealth dramatically. Jahangir was less interested in extending Mughal territory; his reign witnessed the development of a new Mughal style of art and architecture. A connoisseur of paintings and gems, Jahangir commissioned many artworks from the royal workshops. Paintings made during Akbar’s reign celebrated his conquests and the glories of war; those commissioned by Jahangir focused on animals, birds and scenes of the leisurely life at court, with the royal family always depicted in fine clothes and bedecked with gold and jewels.

International connections

Many details of the painting, such as the Persian carpets and the Chinese porcelain on the shelves in the background, show the Mughal empire’s international connections. Foreign influences can also be seen in the style of the painting. The founder of the Mughal dynasty, Babur, brought with him to India Persian artists who created works that integrated local Indian and Persian forms. Jahangir, and his father Akbar before him, welcomed gifts of European prints and paintings from missionaries, ambassadors and traders. The style of this painting combines the colours and detail of Indian and Persian art with the space, depth and modelling of European art.

The Dutch and Portuguese were the earliest European powers to develop trade with India, but in the early AD 1600s the English East India Company was granted concessions by Jahangir which allowed it to set up trading posts there. The Company was keenly aware that it needed the emperor’s support in order secure supplies of spices, tea and textiles, which were in high demand in England. Gradually the Company established a stable and highly profitable commercial presence in India, eventually displacing the Dutch and Portuguese.

By the 1750s, the Mughal Empire was in a process of disintegration due to a combination of weak leadership, economic problems, external invasions and internal pressures from the formation of independent regional Indian states. Although some of these states were economically and politically stable, some of the more ambitious ones sought increased power, were prepared to go to war and were willing to accept European support. The East India Company now had an opportunity for military and political intervention in India, using its private army to settle disputes and exert control. While Mughal Emperors continued to rule in name, the Company was reshaping the subcontinent to suit British priorities. In 1858 the British deposed the last Mughal emperor and the empire that had been at its height under the rule of Akbar and Jahangir was brought to an end.

More information

The Age of the Mughals

The Age of the Mughals: a summary from V&A Museum, illustrated with objects.

http://www.vam.ac.uk/content/articles/a/the-age-of-the-mughals/

The Mughal Empire

BBC Religions: The Mughal Empire. An overview of the empire and its rulers in the AD 1500s and 1600s.

http://www.bbc.co.uk/religion/religions/islam/history/mughalempire_1.shtml

The East India Company

Information about the East India Company and the port of London.

http://www.portcities.org.uk/london/server/show/ConNarrative.136/chapterId/2764/The-East-India-Company.html

Britain and India

Information on Britain and India with original documents.

http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/pathways/blackhistory/india/india_british.htm

The British Presence in India in the 18th Century

http://www.bbc.co.uk/history/british/empire_seapower/east_india_01.shtml

India and the British parliament

The first of a series of five web pages on India and the British parliament.

http://www.parliament.uk/about/living-heritage/evolutionofparliament/legislativescrutiny/parliament-and-empire/parliament-and-the-american-colonies-before-1765/parliament-and-the-east-india-company/

More information

-

The Age of the Mughals

The Age of the Mughals: a summary from V&A Museum, illustrated with objects.

Source: vam.ac.uk

-

The Mughal Empire

BBC Religions: The Mughal Empire. An overview of the empire and its rulers in the AD 1500s and 1600s.

Source: bbc.co.uk

-

The East India Company

Information about the East India Company and the port of London.

Source: portcities.org.uk

-

Britain and India

Information on Britain and India with original documents.

Source: nationalarchives.gov.uk

-

The British Presence in India in the 18th Century

Source: bbc.co.uk

-

India and the British parliament

The first of a series of five web pages on India and the British parliament.

Source: parliament.uk