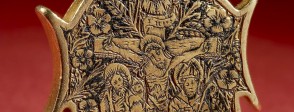

Before showing the pendant, engage interest by telling the story of how a wagoner found the Matlaske pendant in a field in Norfolk. Just at the point where he has pulled it from the mud, break off. Ask the class to think of things they have lost when out and about in open places such as park or the countryside or a beach. Make of list of objects they mention. Discuss what might happen to the object if left in the open. What might an archaeologist in 500 years’ time make of what remained? What challenges might she or he face? Now return to the story of the Matlaske discovery, reveal what the object was after being cleaned and develop the learning from there, possibly using one of the approaches below.

You can use the image on the Matlaske pendant simply as a visual aid to check or reinforce students’ basic understanding of Christian, especially Roman Catholic, teachings regarding the death of Christ’s as payment for mankind’s sins and to save people from the terrors of hell. Explore the role of saints as go-betweens even after their death to help people. After doing this, move on to show that the pendant is much more than just a reminder of Christian beliefs.

Use the image in For the classroom and invite students to say what they can see in as much detail as possible. Ask what more they could tell if they had the actual object, for example, weight, size, signs of damage etc. Then ask them to speculate about what they think it was, when it was made and what sort of person may have owned it and why. At this point encourage reasoning that is based on visual clues rather than wild guesswork. Then explain that archaeologists only make sense of one object by comparing it with others.

Look at the other two pendant reliquaries, the ring and the badge in For the classroom and add a few details about when each was made, what it is made from and how big it is. Students must find as many different ways as they can to group the objects by things they have in common, such as shape, images, material, size, inscriptions, clasps, date. Then develop their reasoned speculation and ask them to devise further questions and lines of enquiry.

Issue either a context sheet or sets of cards with snippets of relevant background information about medieval religion, relics, reliquaries, pilgrimages and souvenirs, St Anthony, ergotism and St Anthony’s Fire. Ask students to do two things: reach their final hypothesis on what the Matlaske pendant is and summarise what they have learned about how archaeologist and historians work with sources.

As an extension of the task above, ask students to say who they think the bishop figure on the Matlaske pendant is: St Anthony, or another saint connected with healing? You might complement study of this object with the Object file: the murder of Thomas Becket (coming in November).

An alternative to using the other objects is to use the links in For the classroom. After students have reached their own initial informed speculation and before explaining anything about relics or reliquaries, show the map of Europe’s main shrines and pilgrimage sites and click its links to Paris and the Sainte-Chapelle. Click on the link within the plan to show the animated panoramic photography of the interior. Explain that this whole building was made as a container for the original crown of thorns worn by Christ. Images of the relic itself are also available online if you search for Crown of thorns, Notre Dame. Next use the link to the video showing details from a German portable altar. Follow this by showing the video about the opening of actual relics from the same portable altar. Discuss what the chapel and the portable altar have in common before inviting students to suggest what this has to do with the Matlaske pendant. They should see how it is a scaled-down, personal version of the chapel and the altar: a reliquary.

These three questions show some different approaches to using the pendant within broader historical enquiries.

Start the enquiry by showing the pendant but only to intrigue the students. Tell students that they can only make sense of this object after they have studied the world in which was made. Follow a sequence of learning that covers religion, social diversity and medieval health in such a way that the Matlaske reliquary should make sense to them by the end. They must round off their learning by preparing their own short podcasts about it, having heard and de-constructed relevant examples from the BBC’s History of the world in 100 objects.

Here the pendant is used simply to help the teacher reveal an example of late medieval piety or superstition or both. This can set up an enquiry that takes in such features as the wealth and power of the church, late medieval teachings and the use of relics and indulgences alongside early stirrings of the Reformation such as the Lollards in England.

Here the focus of study is broader. Using the sources in A bigger picture, students must create displays or digital presentations using various reliquaries from different times and places and plotting them on a map and timeline. They must link each one with a summary of what it shows about the development of the church from the death of Christ to at least AD 1550. By showing the video link about a 17th century English saint and by reminding students how many relics are now in museums not churches, the timeline can reach the present day.